Lost Recipes of the Silk Route

Centuries before planes, maps, and shipping containers, the world was already connected by trade routes carved through deserts, mountains, and seas. Among the many treasures that travelled along these ancient paths – silk, spices, gold, and gems, there was something humbler but equally precious: dry fruits.

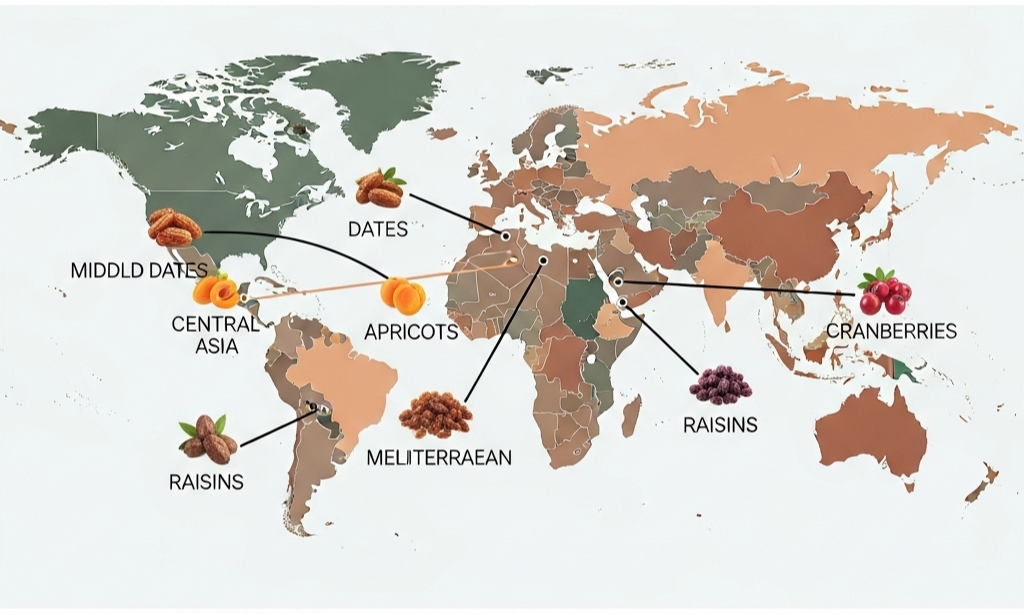

Almonds, figs, pistachios, raisins, and dates were among the earliest commodities that made the Silk Route not just a trade network, but a bridge of culture, cuisine, and civilization. They didn’t just nourish travellers – they shaped tastes, rituals, and relationships across continents.

Let’s retrace this journey and uncover how dry fruits quietly connected the world long before globalization was a word.

The Journey Begins: The Ancient Silk Route

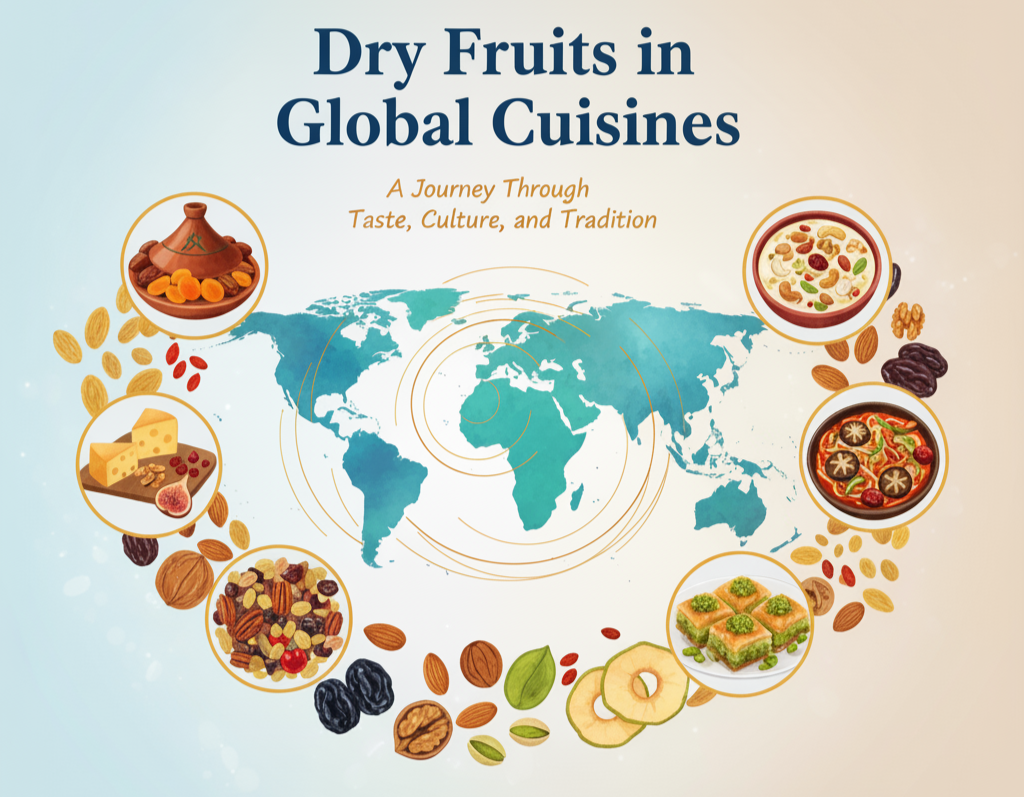

The Silk Route wasn’t a single road but a network of trade corridors stretching from China and India through Persia, Central Asia, and Arabia to Europe and North Africa. It carried goods, ideas, languages, and culinary traditions.

In a time before refrigeration, dry fruits were a miracle of preservation – light to carry, rich in energy, and long-lasting. Caravans and merchants stocked almonds, pistachios, and dates as travel companions across harsh terrains. As they traded these delicacies, they also traded flavors and stories.

Persia: The Heart of the Nut and Fruit Trade

The Persian Empire was a crossroads of luxury goods, and dry fruits were its edible jewels. Persian traders perfected the art of drying figs, apricots, and mulberries under the desert sun.

In royal Persian kitchens, dry fruits weren’t mere snacks they were culinary essentials. Pistachios adorned saffron rice, raisins and apricots sweetened stews, and almonds added depth to sauces and sweets.

Recipes like Khoresht-e Aloo (apricot stew) and Polow-e Morgh (rice with raisins and almonds) travelled with Persian traders influencing cuisines from India to Turkey.

India: Where Dry Fruits Became Tradition

As trade flowed eastward, India became both a producer and consumer of dry fruits. Kashmir’s walnuts, Afghanistan’s figs, and Persia’s pistachios entered Indian markets through these ancient exchanges.

In India, dry fruits were quickly woven into tradition. They became part of Ayurvedic diets, wedding rituals, and festive dishes like kheer, halwa, and biryani. The Mughals, with their Persian heritage, elevated this further introducing rich gravies and desserts layered with almonds, cashews, and raisins.

A dish like Shahi Tukda or Sheer Khurma carries traces of that Silk Route heritage – blending Indian milk, Persian dates, and Central Asian nuts into one royal recipe.

Central Asia: The Caravan’s Feast

In the oases of Samarkand and Bukhara, dry fruits were the centerpiece of hospitality. Travellers and merchants were welcomed with bowls of almonds, apricots, and dried mulberries, served alongside green tea or fermented milk.

The Uzbek Pilaf (Plov) rice cooked with lamb, carrots, raisins, and almonds emerged here. It symbolized the perfect balance of sweet and savory, warmth and strength. This dish later influenced biryanis in India and pilafs in the Middle East, proving that a handful of dry fruits could unite diverse palates.

Arabia: The Gift of Dates

For desert dwellers, dates were life itself. They sustained travellers through long journeys, offered natural sugar for energy, and became a spiritual food especially during Ramadan.

Arab traders introduced dates, almonds, and dried figs to Africa and Europe, spreading both the ingredients and the values of generosity and sharing. The tradition of gifting dates during Ramadan or as tokens of goodwill has survived for over a thousand years making them one of the oldest symbols of hospitality in the world.

Europe: The Sweet Arrival

By the time dry fruits reached Europe, they had become symbols of wealth and festivity. They appeared in Renaissance banquets, Christmas fruitcakes, and medieval pastries.

Monks in monasteries cultivated fig trees, and traders from Venice and Genoa imported almonds and raisins in bulk. These imports inspired culinary creations like:

-

Panforte from Italy – dense fruit-and-nut cake eaten during winter feasts.

-

Stollen from Germany – bread filled with almonds, raisins, and candied fruits.

-

Tarta de Santiago from Spain – almond cake symbolizing faith and celebration.

Each of these desserts, though European in origin, carries traces of the Silk Route’s sweetness.

Lost Recipes and Living Legacies

Many of the recipes from the Silk Route have evolved, some disappeared, and others merged into new traditions. But the essence remains — a shared table where East met West through the language of food.

If you follow the path of a single almond, you’ll find it connects a Persian merchant, an Indian cook, a Central Asian host, and a European baker. Every bite we take today from a Diwali sweet to a Christmas cake carries whispers of that ancient exchange.

A Modern Connection: From Caravans to Gift Boxes

In today’s world, dry fruits still play the same roles they did centuries ago symbols of health, wealth, and goodwill. They travel across continents, now wrapped in elegant packaging rather than camel pouches, yet their meaning remains timeless.

At Kharawala’s, each gift box – be it Uphaar, Royal, Eternia, or Anmol – carries a fragment of this history. It’s a modern reflection of what the Silk Route once stood for: sharing abundance, fostering connections, and celebrating diversity through food.

Final Thoughts

The Silk Route may have faded from maps, but its flavors live on in every kitchen and celebration. Dry fruits, once the currency of empires and lifelines of travellers, now unite us through recipes, rituals, and gifts.

They remind us that food is more than nourishment – it’s heritage, connection, and a bridge between worlds.

So, the next time you open a box of almonds or stir pistachios into your dessert, remember – you’re tasting history, one bite of the Silk Route at a time.